Hello again,

Imogen here with more mollusc goodness for your soul from National Museum Wales. I can’t believe another month has gone, it’s flown past so quickly! For me, this month has been all about getting to grips with freshwater molluscs.

Fabulous Forest School fun

The end of last month I went on a visit to my local TCV office, The Tree Life Centre, where I got to meet some of the lovely staff and catch up with Delyth my nearest Natural Networks trainee. I had fun helping out with some Forest Schools sessions and getting very muddy. The sun even came out, and Liam spotted his first bee of the year, a female carder bee searching for a nesting site. One of the mum’s with the Forest School children also managed to find a shield bug and a ground beetle – an early time of year for them to be about, and a sign that spring was fast approaching. Chatting with Delyth and Jason gave us all some great ideas for how we can collaborate on some projects, and we’re expecting exciting things this year!

TCV selfie! Myself, Liam Olds (both Natural Talent), Delyth Hurley (Natural Networks) and Jason Leck (Project Officer) outside the Tree Life Centre, Bristol

In search of the mouse-eared snail

My journey into fresh and brackish water Molluscs begins… something I have never looked at before. This started with a trip out to one of Gwent Wildlife Trust’s sites, Peterstone Wentlooge Marshes. I was intrigued by this reserve, as it is very different to all the others I might be looking at; a coastal site consisting of mudflats and a small amount of grazing Salt Marsh. This is a very sensitive site, being an important feeding ground for wading birds, so we took care to visit at low tide, when the birds were further out on the mudflats and we could avoid disturbing them from their dinner.

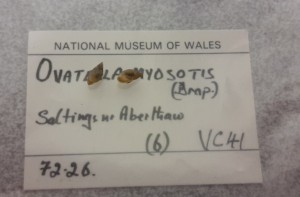

Through a conversation with a stranger on Twitter I found out that the brackish water snail species Myosotella myosotis (Mouse eared snail) is thought to be in serious decline in Yorkshire. The species is restricted to rocky or muddy coatlines, where it shelters under stones and at the roots of salt marsh vegetation. My curiosity was roused, and a quick peek at NBN gateway and chat with Ben Rowson revealed that this species had been found on the coast near Redwick, Newport, 10 miles the other side of the mouth of the river Usk. The presence of salt marsh habitat at Peterstone Wentlooge and how relatively close the site was made us hopeful that we might be able to find the species there. However, despite a careful search, no signs of M. myosotis were found, not even any empty adult shells. This may not necessarily mean the species isn’t found there in low densities, as given the tidal nature of the site and recent storms any shells may have been swept away, but it appears unlikely.

We did find some other small snails crawling about on the mud, so scooped up a couple of mud samples to pick the snails species out of later, as they were so small they need a microscope to ID them accurately. Back at the museum, we sifted out this sample and I was amazed by the number of tiny shells in one small piece of mud! Many were the remains of or juvenile sea shells, but I identified one species of brackish water snail that had caught our eye crawling over the mud as Peringia ulvae

Freshwater Fun!

While at Peterstone Wentlooge, Ben introduced me to sampling for Freshwater molluscs in a nearby reen (drainage channel/ditch) which I had a go at netting. The mud in the ditch was very fine and clay rich, making it a challenge to extract things from and cling to me quite nicely! The reen had been dredged within the last year, with the dredgings left at the side, making it simple for us to go along and pick out all the mollusc shells out of the dried mud. Back at the museum it was time to sit down and start keying out these freshwater species… some were incredibly tricky, and I was really stuck with a few until Ben put me out of my misery and revealed they were sneaky land snails and so not in the key I was using…oh! I did manage to identify a total of 9 freshwater species – not bad for a first attempt, and hopefully some new records for that site.

The freshwater theme continued with a (literally) flying visit of John MacFarlane from Scotland. We took him and Liam out for a fun day out to the lovely Gwent Wildlife Trust reserve Magor Marsh, where despite a mixture of light snow, sleet and sunshine, I got to introduce him to my new favourite freshwater species Planorbis corneus (Great Ramshorn Snail). The visits this month have got me excited and eager for my project of sampling freshwater reens at Gwent Wildlife Trust sites, something I will start to do from mid-April.

Introducing Invasive Species Week

The 26th February – 6th March 2016 was Invasive Species Week which found me joining the National Museum Wales staff at the Welsh Government offices talking to governmental staff about Invasive invertebrate species, what we can do personally to help prevent them spreading, and finding out more about the Check, Clean, Dry campaign.This was an amazing experience and a great opportunity to engage with policy makers and share museum specimens with them.

Exploring under recorded areas

On one of my days off, I got itchy feet and decided to head off to SEWBReC’s Square of the Month. This is a project by the South East Wales local records centre where they high-light 1 km squares which have few or no biological records. This month’s square had a total of 7 records… which is barely anything when taking in to account the fact that it covers all taxa; plants, animals, insect etc. With maps in hand I headed off on a mini-adventure, taking along essential supplies of ID guides, tea and cake. This square was interesting rural habitat; containing a churchyard, plantation woodland and some reens. The reens were on private farmland, so I left them well alone, but in less than an hour wandering around the public access areas of the square I managed to casually record 8 bird species, 5 plant species, and 11 slug and snail species. The majority were common species, but it’s still a lovely bunch of new records for that square, more than tripling the existing amount! All it took was a short wander in the sunshine and some brisk fresh air.

Adventures with Bivalves

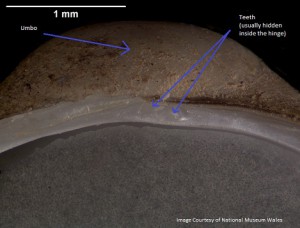

Back at the museum, I decided to start looking at fresh water bivalves, a completely new group of molluscs for me! These can range from large species, such as the Margaritifera margaritifera (Freshwater Pearl Mussel) which matures at 110mm, to the tiny species, such as Pisidium (Pea) mussels that mature at 2-5mm! The identification features are also very different to slugs and snails; taking in to account the position and shape of the ‘umbos’ (the bumpy bit towards where the two shell halves join), surface textures of the shell, presence or absence of shells pores, and sometimes the shape of the internal hinge. For the 16 tiny Pisidium species there are very few well-defined and many overlapping shell characteristics between the species. This means identification is best with whole mixed samples, not single individuals, so that characteristics can be compared against each other. They are such a difficult group to identify that most freshwater survey protocols advise against even trying to identify to species. Even the staff at the museum find them very challenging… making me determined this year to attempt to master then!

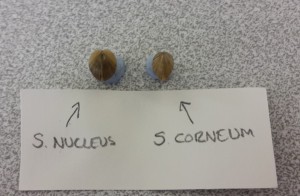

With this in mind, I was lulled into a false sense of security by 4 Sphaerium species, larger at 10-25mm and straightforward to identify… or so I thought. After identifying some of these as Sphaerium corneum from the reen at Peterstone Wentlooge, I suddenly discovered that this distinctive looking species has actually been divided into two species in 2004: S.corneum and S.nucleus. S.nucleus is fatter and more rounded, with dense pores on the umbonal region, and different shaped teeth inside the shell hinge. Still sounds fairly straight forwards hey?… until I discovered an article published in 2008 about how S.corneum can occasionally have dense pores too, all these features may vary, and that there may be another species in the UK sharing a combination of these features…argh!

Unfortunately I only had a limited selection of published photos to rely on to help me spot these features as none had been identified in the museum’s collections yet. Unphased, I decided to go on a hunt for likely specimens – proving to be a steep and very interesting learning curve in bivalve features! Taxonomic changes and realisations like this one are another example of why museum collections are so important. Even a species considered common like S.corneum is vital to have in a collection. Now we can go through them and identify S.nucleus from collected material, and find out where it has been found historically in the UK. From this we gain an idea of how habitats and distributions may have changed over time.

For me, it also illustrates why photos can never really be a truly effective replacement for having an actual specimen. A photos angle, lighting and even knowing which part of the animal is being shown, can make key identification features hard to see. Though saying that, I did have a great time taking photos to send off to the UK Sphaerium expert for a second opinion.

Stay fresh guys!

Imogen Cavadino

Natural Talent Trainee: Non-Marine Molluscs

Don’t forget you can keep up to date with my daily antics on Twitter here or here.

A massive thank you to the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation for funding this amazing programme. Find out more about them here.

Also to National Museum Wales for hosting my placement. Be sure to drop in for a visit to the public collections when you’re in Cardiff!