For most part, it has been a lovely April. The Met Office report that we have had a +35% increase in sunshine hours and around 40% reduction in rain. This is good news as the insects are enjoying the good weather too and are starting to emerge from hibernation or dormancy. Some insects overwinter as adults and others as juveniles. The winter months can sometimes be a good time to find those that overwinter as adults as they are much likely to be static sue to the colder temperatures providing you know where to look. For those that overwinter as juveniles, it is often best to leave them be until early spring and this is the perfect time to collect late stage juveniles to rear through to adulthood. Exactly what I have been doing whilst out and about in the woods this month.

This technique is often employed by entomologists as adults are generally much easier to identify than their younger counterparts. In fact, for some insects, this can be the only reliable way to collect them and discover host plant/fungi associations. Those insects that hide themselves away in accessible places such as deep between gills on the underside of fungi, inside plant stems, including trees or sandwiched between the layers of a leaf would be prime candidates. The majority of leaf miners are Lepidoptera (moths) and Diptera (fly) species but the Coleoptera (beetles) are also represented. For example, Trachys minuta (see Figure 1) is a small beetle of around 3mm that mines in Hazel and Willow leaves.

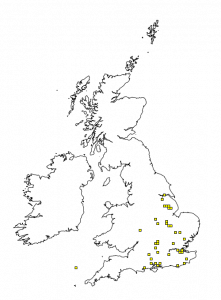

It is reasonably rare with a distribution roughly south of a line drawn between the Severn estuary and Hull (see Figure 2). T. minuta is a member of the Buprestridae family, otherwise known as the jewel beetles. Most other beetles of this family are wood borers, many of which are currently restricted to the southern part of the UK just like T. minuta.

Figure 2: T. minuta distribution (https://data.nbn.org.uk)

Many saproxylic beetles are not actually capable of directly digesting cellulose or lignin, the main components of wood. Instead, they get nutrition from the wood once the fungi have moved in and begun the decay process. There are at some notable exceptions to this, for instance, many of the longhorn (Cerambycidae) beetles but also Agrilus species (Buprestridae) are able to feed on living wood. They most likely do this by having a symbiont gut bacteria. A paper by Vasanthakumar et al. (2008) reported that three gut bacteria were identified in Agrilus planipennis (Emerald Ash Borer) that were able to break down cellulose. This beautiful beetle is, however, on the Forestry Commission’s list of exotic pests to look out for (more information here). So, if you do happen to see one – please report it!

But I digress – back to rearing! Perhaps the most important thing to consider is the habitat in which the larvae would live in the wild and try to replicate the important aspects of those conditions. Providing the right substrate and maintaining the correct moisture level is often critical for success. As I have discovered this comes down to experience, the tipulid (cranefly) larvae in Figure 3 turned mouldy as the humidity inside the jar was too high. There must be adequate ventilation (punctured holes perhaps covered with mesh depending on the size of the species) to help prevent condensation and avoid over enthusiastic watering with the spray bottle!

Temperature is likely to be less of a problem as many insects will be fine at room temperature but beware of that sunny window as it will also affect conditions inside a rearing pot by producing rapid changes and/or extremes of temperature and cause excessive drying or possibly condensation.

I have successfully reared the cardinal beetle Pyrochroa coccinea. The larvae of this beetle where collected from under the bark of beech that was stacked in a log pile. They were placed in the container with the collected bark and provided with some soil substrate to encourage pupation. After three-four days they had started to darken in colour and this is often a sign of emergence on the way. Sure enough, the following day that was exactly what happened and Lo and Behold the gorgeous looking adults appeared (see Figure 4).

Another success story was the muscid fly Phoania goberti seen in Figure 5 and a Malthinus soldier beetle (Cantharidae). Many more currently “in progress” including some rat tailed maggots (Eristalis drone fly larvae), more on those once they have emerged.

I would thoroughly recommend this activity for all budding entomologist or curious nature lovers. It is a very rewarding and exciting experience to watch something emerge. Little kit is required, any old plastic or glass container (ice-cream tub, jam jar), a pair of old tights to cover the ventilation holes and a clean water spray bottle will do the trick. It would be great to know your stories and if you are on twitter please let us know by using @Natural_Talent or @Ceri_Watkins.

Reference – Vasanthakumar, A., Handelsman, J., Schloss, P., Bauer, L. and Raffa, K. (2008) Gut microbiota of an invasive subcortical beetle, Agrilius planipennis Fairmaire, across various life stages. Molecular Ecology and Evolution, 37(5) pp.1344-53.