When I first seen the advertisement for a ‘TCV Natural Talent Trainee – Colliery Spoil Habitats’, I honestly couldn’t believe my eyes. I have long but dreamt of an opportunity to work on my favourite British habitat and share my enthusiasm for these biologically interesting, but often overlooked, landscapes. Having lived in the South Wales valleys all my life, I have been exploring colliery spoil sites from an early age. Over the years, I have recorded an astonishing array of wildlife and these sites have been home to some of my most memorable wildlife moments. If not for colliery spoil, it is likely I would not have developed my interest in wildlife and thus be in the position I am today; for that I am very thankful. It is fantastic that The Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, The Conservation Volunteers, and the National Museum Cardiff have given me the opportunity to learn more about the habitats I love; thank you so much!

Based at the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, my traineeship focuses on the diversity of invertebrates and lower plants that can be found on colliery spoil habitats. Since this is my first Natural Talent blog, I thought I’d kick things off with a bit of Welsh history to set the scene.

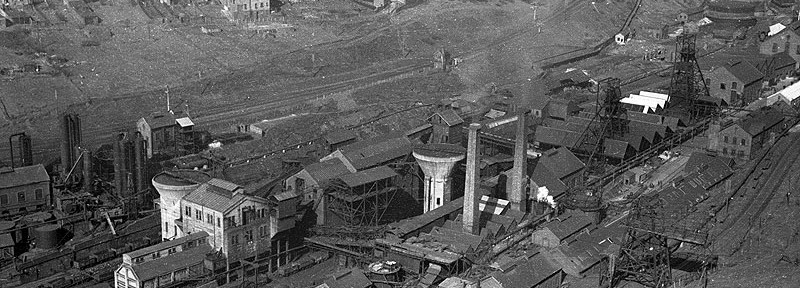

As the Industrial Revolution ‘took off’ in Britain, so too did the demand for coal. As Britain began to industrialise itself, more and more coal was needed to produce the steam power on which industry depended. South Wales was well supplied with coal and its high demand brought about a ‘boom’ in its coal industry. Attracted by the availability of work and better wages, people flocked to the South Wales valleys from all over Britain. At its peak, over 250,000 men were employed in the industry. With large deposits of high quality coal, the Rhondda became the centre of the coal industry with 53 working collieries in an area only sixteen miles long! In 1913, 57 million tons of coal came up from the mines and South Wales produced one third of the world’s coal exports.

The effects of World War I and the post-war depression, however, brought about a decline in the coal industry. By 1936, 241 collieries had closed and the workforce had halved. Following a brief revival post-Second World War, the industry continued to decline throughout the second half of the 20th century. By the end of that century, just one deep mine remained in Wales. The coal industry, the most important industrial, social and political force in modern Wales, had all but vanished.

Following their closure, many colliery sites have since remained abandoned. This abandonment and subsequent low-level disturbance has enabled habitats and wildlife to colonise these once baron industrial landscapes. Often overlooked and under-appreciated as biologically interesting places, many colliery spoil sites now support habitats and wildlife of considerable local biodiversity value.

By undertaking fieldwork at sites across South Wales, I hope to gain a greater understanding of colliery spoil habitats and the intriguing wildlife they support. Through links with an existing OPAL Community Scientist post, I also hope to promote colliery spoil sites as biologically interesting places worthy of the landscape they occupy. I am extremely excited about the prospect of getting out into the field and finding some truly amazing wildlife, once spring arrives (hopefully soon!). I’ll keep you updated on my work and what I discover on my adventures.

Thanks for reading!

To find out more about the Natural Talent Traineeship, the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, and National Museum Wales, please follow the links below.

Find out more about Natural Talent

Find out more about Esmee Fairbairn Foundation

Find out more about National Museum Wales