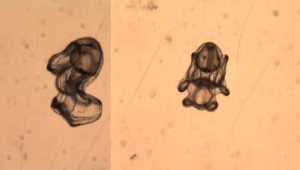

Over the last few weeks Rosie Foster (my fellow zooplanktonologist at SEPA) and I have been working furiously to try and finish analysing all the zooplankton samples from this year. It has been amazing to see the changes that take place in the plankton communities throughout the year from the increase of amazing jellyfish in summer months to the build-up of female Acartia clausi copepods that tough it out over winter whilst most of the males die off. To an untrained eye the male and female look really similar but once you know what to look for they are quite easy to tell apart. First, the adult females have a swollen first segment of their urosome or tail. This is called a genial somite and can sometimes have eggs or spermatophores attached. The males often have a more “boxy” head as seen in the picture below and also have adapted bent, hinged antennae (termed “geniculate”) which helps them to grasp onto females. The last pair of legs of the males is also often adapted for delivering spermatophores to females. This feature of many copepods is often really useful for identification – As seen in these legs there are two bumps which is the only way to distinguish between Male A. clausi and A. discaudata which has only one bump.

Another type of zooplankton I’ve enjoyed seeing change over the summer season is echinoderm larvae. There are about 7000 species of echinoderms and they are quite unusual in being one of the few phyla with all marine species. The word echinoderm actually means “hedgehog skin” and they have really varied, beautiful larvae – another reasons I love finding them in samples. Another reason I like them is that they are a brilliant example of meroplankton (plankton that only spend a part of their life cycle as zooplankton) and look completely different from their adult forms. Starfish are one of three classes within the echinoderm phylum, the other two being brittle stars and sea urchins.

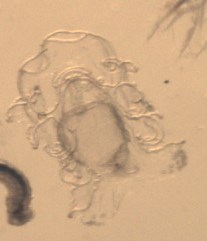

Starfish, the best known of the echinoderms, have two larval forms the first called bipinnaria followed by brachiolaria when the arms begin to develop.

Brittlestars are less well known than starfish (as they inhabit deeper waters) but do resemble them with 5 arms but they are longer and more slender. This has led to them also being known as serpent stars from their latin class name Ophiuroidea meaning “serpent.” A brittlestar larvae is called an ophiopleutus and has 4-6 calcareous arms making it quite distinctive from the gelatinous starfish larvae.

The third class of echinoderms are the sea urchins and there larvae are termed echinopleutus and can be quite hard to distinguish from ophioplutei in early stages.

SEPA’s sampling year runs from December to November so the sampling of the sites for my project in the Clyde have finished. Yesterday I was sampling in St Andrew’s for the new sample plan which was very choppy but lots of fun and the first time I’ve been on one of SEPAs 5.3m RIB (Rigid inflatable boat) called Swift.

Hope everyone has a brilliant Christmas and New Year. Having finished our samples I have an entire season worth of data to play with when I get back so a statistics filled January awaits me on my return!