Hi all,

So, where was I with my last blog? Ah yes, just arrived in Galloway and enjoying a few days of very nice weather. Well, after an eventful holiday in Skye, I returned to Galloway and the Cree Valley Community Woodlands Trust.

I’ve been getting involved with CVCWT’s WIAT work (Woods In and Around Towns) and Holm Wood Riparian Project. As well as doing some of the organisation for a water vole project conference in November, I’ve also been given the task of designing a new interpretation panel to let visitors know about the water vole colony at Holm Wood.

I have actually seen a water vole, once, by accident. I was out doing one of my least productive things: looking for otters. I strongly suspect that going out looking for water voles in future will increase my chances of seeing an otter. Might as well give it a shot – the odds can’t get any worse!

Anyway, I was surprised how big the water vole was; it looked like a swimming guinea pig. On the Small Mammals course at Kindrogan last week (which I can’t recommend highly enough), we went hunting for water vole field signs amid very beautiful scenery which distracted a few unfortunate people (Kate!) from watching the bog. This was the first time I’d seen water vole burrows, grazing signs and latrines. A very interesting experience! They had made a complex network of burrows and runs through the grass. I kept thinking I was bound to step on one.

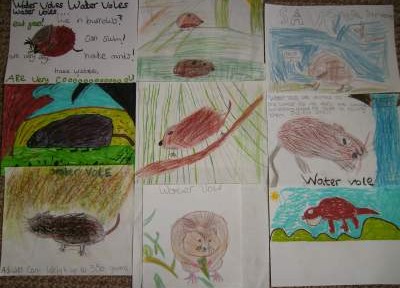

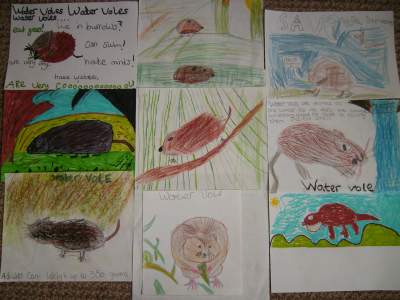

So, my challenge was to get some local children to help me illustrate the water vole panel. Penninghame Primary School obligingly allowed me to come in and work with the P6s for the afternoon. We had a great time! (Well I did anyway.) The children, newly transformed into homeless water voles, had to decide what they would look for in a new place to live, and then build imaginative new homes out of whatever they could find in the playground. They came up with some nice ideas.

Back in the classroom, the artwork commenced. I was left wondering what I would have drawn at that age…. I also liked the fact that one of the children spelt my name ‘Jood.’

Now I have the very difficult decision of choosing which pictures will feature on the panel. Maybe you can help? I’ll put up some pictures of my favourites. Spot the one with the dinosaur influence.

In a couple of weeks I’ll be leaving this side of Dumfries & Galloway and heading back to RSPB Mersehead. I’m looking forward to catching up with the barnacle geese, now back from their summer in Svalbard. I might go with them next year – chances are it will be drier.

In a couple of weeks I’ll be leaving this side of Dumfries & Galloway and heading back to RSPB Mersehead. I’m looking forward to catching up with the barnacle geese, now back from their summer in Svalbard. I might go with them next year – chances are it will be drier.

Something else I attended recently was the Watson Bird Festival in Dalry. I went along to some lectures about hen harriers in the UK. I got a bit of a shock. Though I had heard that this is one of the most threatened birds in the UK, I hadn’t realised quite how bad the situation is. I also can’t get my head around why this should be the case.

Hen harriers are ground-nesting birds of prey. During the breeding season, they are attracted to grouse moors for two straightforward reasons:

1) Unlimited food supply: having all these red grouse chicks running around is perfect for raising hen harrier young

2) There are hardly any predators about, thanks to highly committed gamekeepers shooting, trapping and poisoning virtually anything that isn’t a red grouse. (Apologies for this sweeping statement.)

You see the problem: hen harriers eat red grouse. Unfortunately, gamekeepers will not tolerate anything that reduces the number of grouse on the moors, as this will be detrimental to the privileged few who enjoy driven grouse shooting. Instead of supporting breeding hen harriers, this year the English grouse moors did not see a single hen harrier chick fledge (only one pair even attempted to nest – see BBC article). The species faces extinction on the British mainland, not in the future, but now.

In the interests of putting both sides forward, I’ll concede that hen harriers are eating money by eating grouse. But read on. Dr Aly McCluskie, of the Langholm Moor Demonstration Project, described how diversionary feeding reduced predation of red grouse chicks to just one chick over 5 years of study (100 hours of observation per year).

Diversionary feeding involves putting out alternative food every day for the 2-3 months that the harriers are breeding. Ok, there’s a cost involved, plus it takes time to come and lay out all the carrion. But the cost is very small (we’re not talking about feeding them steaks here), and it was calculated that diversionary feeding occupies roughly 10 minutes per day.

Would you like to guess how many gamekeepers have decided to give diversionary feeding a go? That’s right. None. It seems nothing can beat the easiest option – firing a quick shot.

I understand the conflict of interest, but how can this be happening when a workable solution has been found? Even the law doesn’t seem to be helping to stop this persecution – as it’s almost impossible to prosecute successfully, people are getting away with illegally killing birds of prey (not just hen harriers).

I’m pretty sure that there are more people in the UK who like birds than people who go driven grouse shooting.So why aren’t our voices being heard?