Hi readers! So month number two of trainee life has been wonderfully hectic and full of lichen!

I was lucky enough to go on a training course all about lichen and how to inspire and engage others with lichen, and during this course it was me who ended up becoming inspired and obsessed with lichen! This course was run by the lovely Francis Stoakley, a former TCV Natural Talent trainee who is now a lichenologist and general champion of lichen!

So what is lichen? They grow on almost anything, anywhere, and we probably see them every single day. Lichen is not a plant, it’s actually a combination of two different organisms (living things), a fungus and an algae, working together to create a mini-ecosystem that can feed itself, and grow anywhere. Algae contains chlorophyll, like a plant, and can therefore photosynthesis (make food for itself from the sun). A fungus however cannot produce its own food, it has to source it from elsewhere, usually by forming a relationship with another living thing, like a tree, in which they assist the tree in extracting nutrients from soil and in return receive food. Lichenization, the making of a lichen, is the result of a fungus working with a algae in a mutually beneficial relationship, in which the algae produces and provides food for itself and the fungus and in return the fungus provides the algae with a protective structure in which to live. PHEW.

There are a number of ways in which you can visualise and explain this complex ecological relationship; here is me and some fellow Natural Networks trainees demonstrating just one of them:

So lichen is a fantastic indicator of air quality as it is very sensitive to nitrogen and ammonia in the air which are caused by traffic, industrial, and agricultural pollution. You can look at different species of lichen to work out what the air quality is like in your local area. A general rule is that if you find lots of bushy lichens, the air is clean, whereas if you find mostly crusty and yellow lichens and no busy ones at all it suggests the air is polluted.

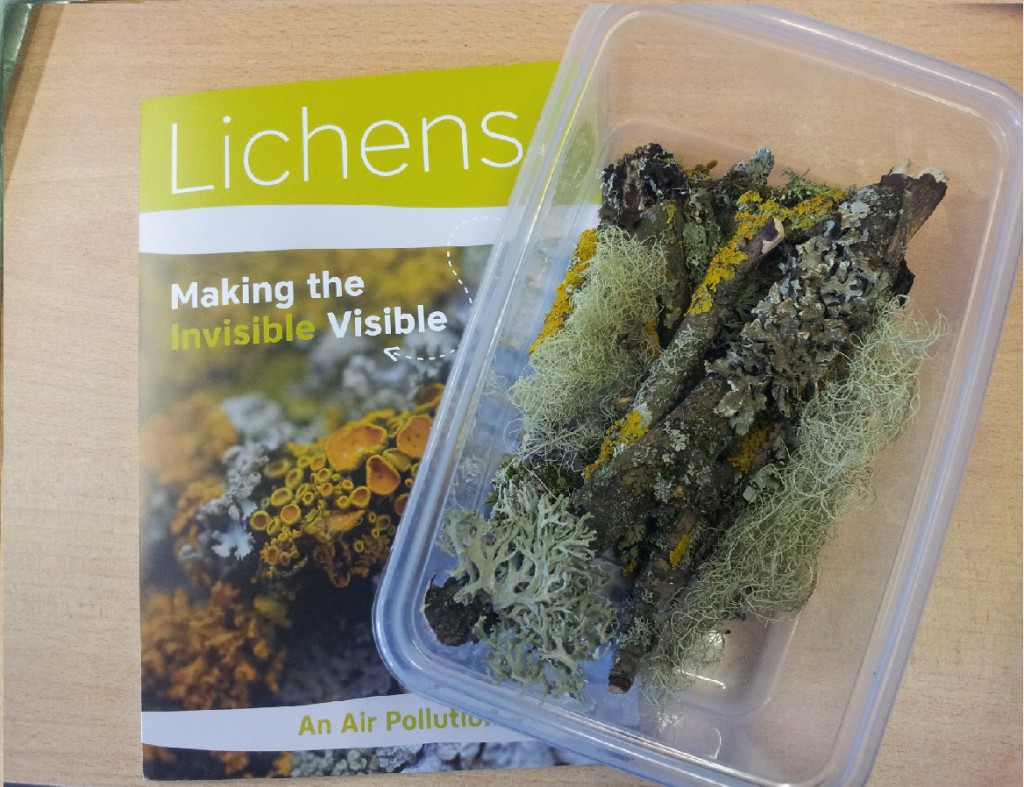

As part of British Science Week my colleague, TCV’s Citizen Science Coordinator Amanda Malcolm, and I visited St Mary’s Primary School in Maryhill, Glasgow, to deliver an education session to a class of ten year olds that would introduce them to the world of lichen and use it to help them understand the importance and impacts of air quality. It became clear that this was a group of children who didn’t often have the opportunity to spend time outside, playing and exploring, away from video games and home stresses. I was amazed and very encouraged by the enthusiasm that some of the children had for the subject, and they used scientific names of lichen species such as Melanelixia and Xanthoria very confidently.

But I haven’t just been immersed in the tiny world of lichen this month. I also took part in a Forest Skills course where we learnt some basic bush craft skills like building fires and tying knots and I whittled a mushroom which definitely looks like a mushroom and nothing else.

Myself and many of the Scotland based trainees managed to get together for another British Science Week event at the Maryhill Hub Community Garden. We set up little table top laboratories with lots of exciting creatures to look at including pond beasts, bugs, worms and of course my friends the lichens made an appearance! Children and adults came to encounter our little specimens from the natural world and it was a beautifully sunny day!

And now for the bees! The Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh hosted a Bumblebee training day with Bumblebee Conservation Trust’s Helen Dickinson, who taught us all about the world of bumblebees and how to identify and survey them. There are about 275 bumblebee species in the world, with 24 of them found in the UK. They evolved in the Himalayas and are adapted to living in colder climates, which is why they love Britain, and why they are furry!

I went on a wildlife walk with some RSPB members earlier in the month where we were lucky enough to find a tree bumblebee! A very good record for Scotland.

Bumblebees are an iconic species and make a pretty good ambassador for insects when it comes to public engagement. People aren’t as afraid of bumblebees as they are of other insects, these chunky, furry, bumbling little beasts are cute and relatively common, giving people a chance to connect with them and enjoy them. I have always liked bumblebees but I have never been able to get up close to one long enough to see their faces, their legs filled up with pollen, or their wings that seem too small and delicate for its fluffy body. They are beautiful! And a little sleepy bee sat calmly on my hand which was the highlight of my day!

Watching people loose themselves in the hunt for bees, jumping up and swishing their nets, was a joy. The whole process from catching your bee, being able to study it up close, identifying it, and then letting it get back to work on the flowers, was incredibly satisfying.

So what have I learnt this month?

I have learnt that bumblebees very rarely use their sting on people, and if they do it does not kill them (this only happens to honeybees).

98% of flower rich grassland, a bumblebees favourite foraging habitat, has been lost since the 1940’s. This is due to changes in agriculture becoming more intensive, the use of pesticides, cutting grass multiple times a year, heavy grazing, and the removal of hedges. Find out how you can help bumblebees.

The two wildlife experts I have met this month, Francis (the lichen lady) and Helen (queen of the bees), have taught me that no matter how inaccessible a species might appear, effective public engagement can turn any subject, whether it be lichen or insects, into an exciting new experience for someone. All you have to do is get people to pay attention and notice the nature around them, explain some of the mind blowing things it can do and provide them with an opportunity to interact with it, and then the nature will sell itself.

Beehave yourselves,

Jess.