TCV is currently working with the Forestry Commission Scotland as part of the Scotland Counts Project to produce a new Citizen Science project all about Deadwood! How exciting! This first blog will give you a bit of background information about deadwood and why it needs our help 🙂

So what exactly is Deadwood? And why is it dead good?

- Deadwood is a tree or part of a tree that has died and is in a stage of decomposition.

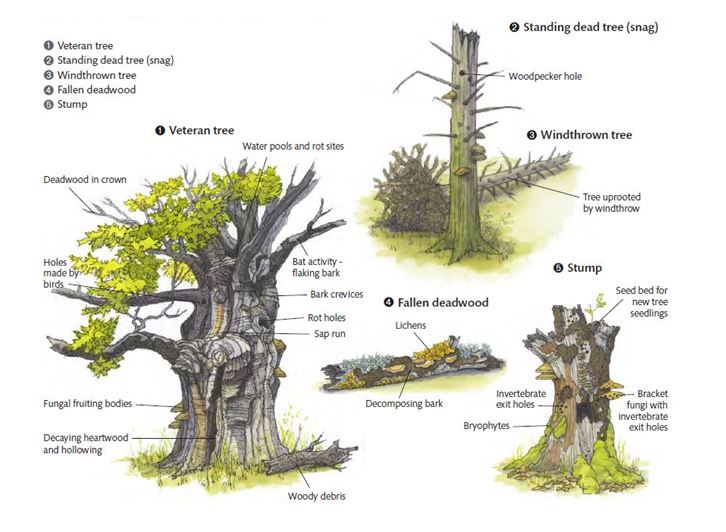

Here are five different types of deadwood (figure 1):

- Deadwood is extremely important to the health of woodlands and even us humans! It plays a big part in nutrient recycling. As plants grow they take nutrients from the soil to help them thrive. If the plant is then removed from that soil, as it often is when you are growing vegetables to eat, then those nutrients are taken away, which is why farmers have to add nutrients back into their soil with compost and fertilisers. In a more natural environment like a forest, where plants like trees are left to grow and die, then the dead wood from the trees will slowly release nitrogen into the soil as it decays for other plants to use.

- Deadwood also acts as a carbon storage system, capturing the carbon that the tree has taken in over its life and locking it into the ground to prevent that carbon being released into the atmosphere, which is a cause of unnatural global warning.

- Fallen deadwood also helps the stability of woodland soil and helps prevent soil erosion.

- Last but definitely not least, deadwood is an important microhabitat for hundreds of wildlife species and is used by birds, mammals, fungi, plants, amphibians, reptiles, insects, and even fish! Ancient woodlands are thought to have the most variety of plants and animals of all the UK habitats and40% of woodland wildlife species are dependent on deadwood at some stage of their life. This includes living on or in the deadwood, eating it, or eating the things that live and grow on it. There are some very intriguing relationships between specific living things relying on very specific types of deadwood, making deadwood home to some of the rarest species on earth. For example, the pine hoverfly only breeds in wet pockets of decay on scots pine tree stumps, and the black tinder fungus beetle only lives on the fruiting bodies of the tinder fungus which only lives on dead birch trees.

It’s these very specific relationships that give deadwood such a great biodiversity value, because there are so many species of trees decaying and different rates and stages and shapes and sizes, it has enabled thousands of other living things to take advantage of these different stages, and take advantage of the creatures taking advantage of deadwood!

But it’s these very specialised niches and relationships that mean deadwood is particularly vulnerable to human activity and environmental change.

Threats to deadwood habitats:

- Removal: Deadwood makes great firewood and is often removed from woodlands to be used as fuel. Deadwood is also removed from parks and public woodlands as it is thought to be ‘messy’ or even dangerous as it is thought that it could harbour pests and diseases, or fall on your head. Some land managers feel there is a need to be in keeping with this public perception of tidiness, but unfortunately wildlife, and deadwood, will not thrive in a tidy park or woodland garden.

- Uniform Age and Species Structure: Many of our woodland areas in Britain are actually forestry plantations. This involves lots of trees (mainly conifer species) being planted all at the same time closely together, so that the trees produce long straight timber that can be harvested and used for building. This is great for timber production, but the problem is that it means all the trees are of the same species and same age. In natural woodland the trees would be a mixture of those that are dead or ancient veteran trees right down to saplings which would host a healthy variety and covering of types of deadwood.

- Loss of traditional woodland management: Woodlands are one of the few natural habitats in Britain that have historically benefitted from human activity. Traditionally our woodlands were managed to produce a variety of fuel and building materials, food and hunting opportunities. Different traditional practices such as coppicing and pollarding (cutting trees to so that they sprout several poles of flexible wood rather than one long piece of timber) meant that areas of woodland where opened up, allowing more light to the woodland floor and therefore encouraging more ground flora. Regular and varied harvesting also meant that many deadwood habitats where created. Sadly there is no longer a demand for these woodland products and activities, it is now cheaper to buy timber from abroad, people now use fencing rather than coppice poles, and the public prefer to buy their food from shops rather than forage it. This has led to woodlands becoming less bio-diverse and the reduction in deadwood certainly has a hand in this.

- Fertilisers and Pesticides: Many large farms and plantations spray pesticides on their crops. These pesticides can very easily be absorbed by deadwood which then kills any invertebrates living within it, or animals that then eat the invertebrates.

So it sounds like deadwood, and all the creatures that love it, could do with a bit of help, to get more people excited about deadwood and its protection.

This is why we in the TCV Citizen Science team have been working to produce The Dead Good Deadwood Survey!

The reason we have done this is to create an educational tool kit that will help people understand the benefits of looking after deadwood whilst also providing us and them with new information about our local woodlands and green spaces. Keep an eye out for our next blog to find out how exactly you can survey deadwood and improve deadwood habitats, but for now, head out and see if you can spot some dead good deadwood!

Picture references

Figure 1. Forestry Commission (2012) Different types of deadwood found in forests and woodlands [Illustration] At: Jonathan Humphrey and Sallie Bailey (2012). Managing deadwood in forests and woodlands. Forestry Commission Practice Guide. Forestry Commission, Edinburgh.